This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

A sense of exploration is at the heart of the work of the American-Australian artist and photographer Brooke Holm. “Catching planes between Australia and the US [as a child], I remember looking out the window, looking down and being fascinated – pressing my face against the window just to look down at everything below. For some reason that view, that perspective, has always fascinated me.”

The process of capturing the natural world is at odds with the confines of the photographic studio – the environment in which Holm trained as a photographer – as it offers ultimate control, a God-like ability to change the light, setting and mood as you please. However, in the natural world, Holm is “at the mercy of the elements. When it comes to shooting nature – you have to be very flexible and very open – you can’t plan one day to shoot because it probably won’t happen…”

From a height and in a helicopter, Holm surveys the land, searching for her composition – but before she ascends, her search begins with Google Earth: “I’ll do a reconnaissance mission[online], looking over different areas, zooming in and scrolling around to see what’s going on. Usually the visuals are the first thing that will drive me [to explore a particular area], and then I’ll start digging further to find out what’s possible in terms of logistics, aeroplanes and pilots to understand how accessible it is.”

The writer and Art Historian, EH Gombrich noted, on the invention of photography, that “the camera helped to discover the charm of the fortuitous view and of the unexpected angle,” and Holm’s work certainly offers that – a perspective that most will never experience themselves, from the ground.

Taking advantage of advancements in technology – from flight to high-resolution digital photography, and even the custom-made gyroscope to which she mounts her camera – Holm’s love of modern technology is not all-encompassing. Avoiding the use of drones, the photographer prefers to experience the landscape in person, no matter how extreme or hostile it may be. “I only shoot from the air – I’m not against drones as a concept, but I do feel like there’s something different in it for me when I am looking down at it myself versus looking at it on a screen. [When you’re in the plane] you can feel the elements, you feel the wind whipping your face – I’m very in the moment.”

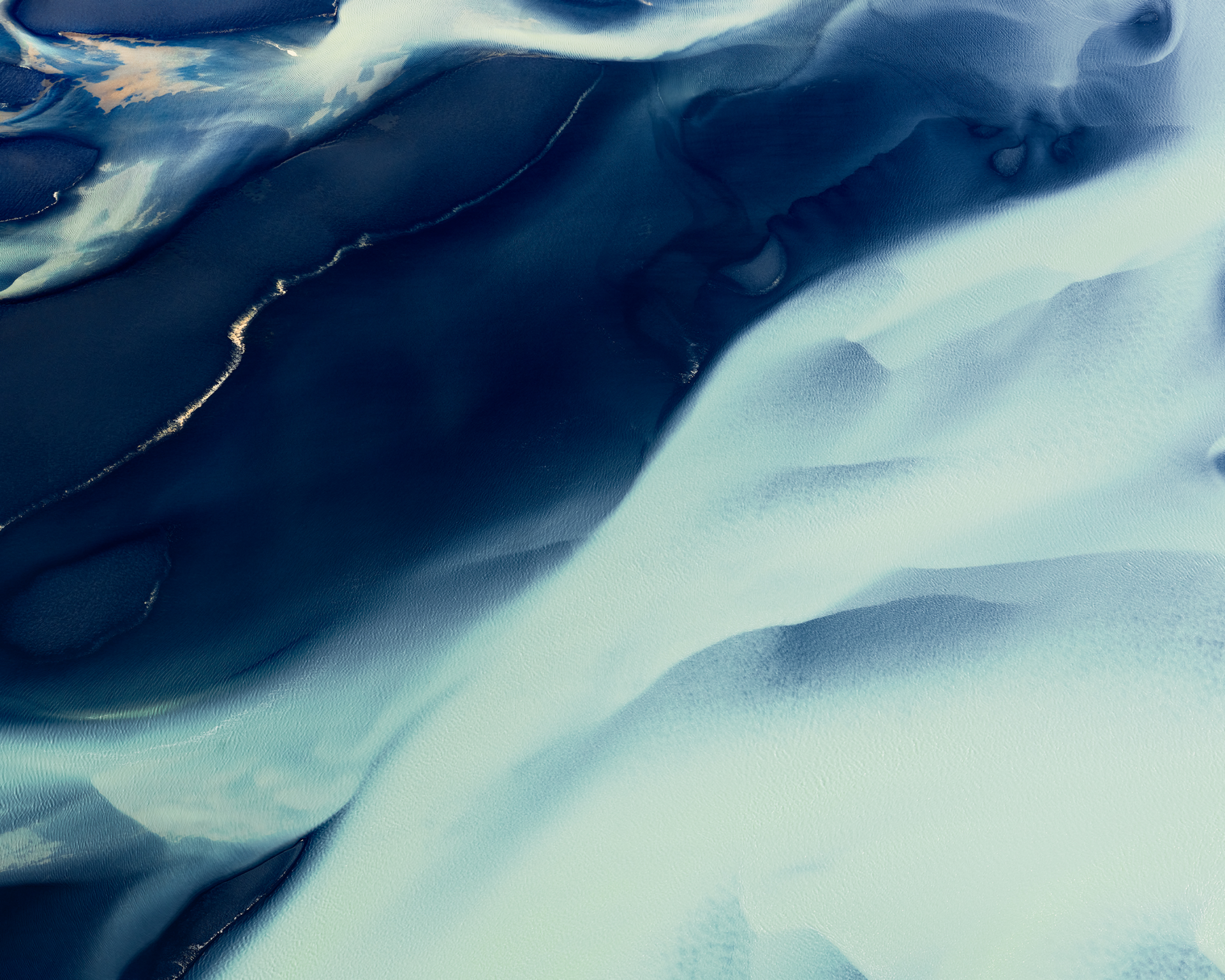

Holm works with the pilot to achieve what she wants, “asking them to go higher or lower, to twist this way or bank that way. I almost always have the plane on its side because I want to shoot straight down rather than across, to have a more abstract result. I don’t like people to know exactly where [the photograph has been taken] as my work is more about the intimate details of a place, that’s what I’m drawn to.”

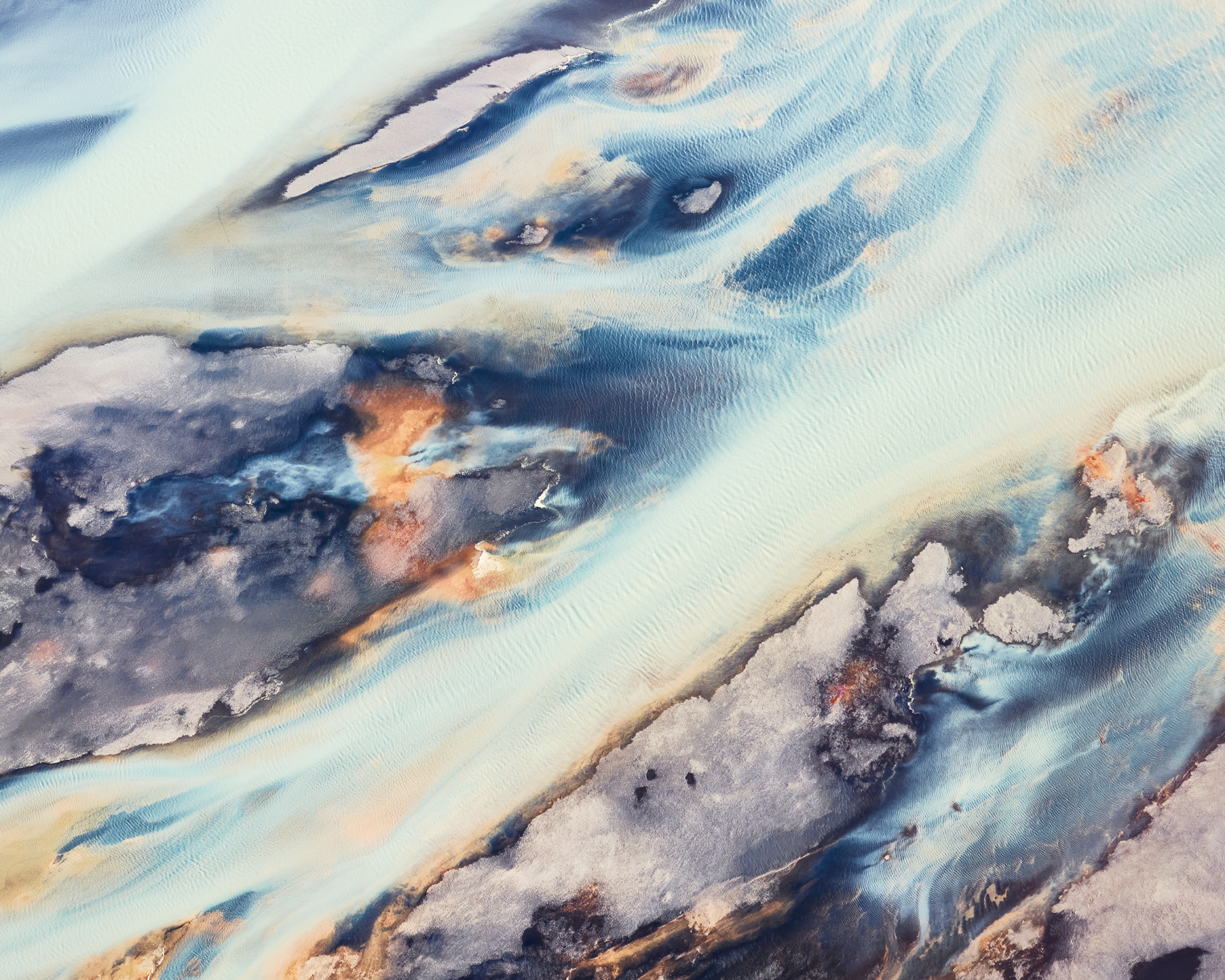

From this perspective the landscape feels unknown and otherworldly, at a distance it is altogether more abstract and painterly. The work of Helen Frankenthaler comes to mind, her large canvases awash with colour, their surfaces composed of watery, diffused shapes -however, Holm’s photographs are not pure abstraction, they are precise, high-resolution descriptions of a particular place.

“The landscapes are incredible in Australia – like someone has thrown paint from the heavens”

Avoiding the clinical or scientific – existing as art rather than geological survey – Holm skillfully deploys the tools at her disposal: light and composition. “If you shoot first thing in the morning or last thing in the day, you get the golden hour – which gives really beautiful shadow and light. It’s very shapely, especially when I was in Namibia on the sand dunes, you’d get one side of the dune in complete darkness and the other in complete light, so if that’s what you’re going for then that’s the time to shoot. But there’s also something very beautiful about neutral light; something a little more diffused, in the middle of the day and a tiny bit overcast – for colour that can be really beautiful and it removes the sharpness of shadow. If you shoot with a bit more diffusion – light that is less harsh – then the images tend to look a little more painterly.”

Translating the magnitude of the natural world into a photographic image, Holm presents her work on a large scale, measuring up to two metres in length. “The scale is important because when you’re looking at something large you feel like you can step into it – you can almost step through it and be teleported into that place. [With large artworks] you’re removed from where you are, and taken to another world.”

“[My work] takes you out of the everyday for a moment”

Much like an impressionist painting, Holm’s work offers the viewer two different readings, being both figurative and abstract depending on your distance from it. What seem at first to be flecks of paint or pigment, reveal themselves to be birds in flight, and, up-close, the painterly markings are the result of purely natural phenomena.

Within those details, buried within the larger picture, “there are little remnants or traces of the human. In the ‘Mineral Matters’ series, for example, you can almost see human footsteps dancing around the edges of these incredible glacial rivers… The perspective I like to shoot from has the essence of people, but they’re not the main focus. Likewise, humans are a part of this planet that we live on, but they’re not the centre of the earth.”

Attracted to places that are sprawling and uninhabited, Holm has travelled frequently to the Arctic – including Iceland, Greenland and Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. “I have a fascination with the North. It’s a very humbling place. It’s also changing rapidly, so it’s important to work up there because it’s going to be completely different in the next 20, 30, 50 years – or even sooner. As an artist, I feel like there’s more urgency to spend time in a place like that.”

The striking icy blue-toned whites of the arctic are off-set in further series, including ‘Salt and Sky’ – a survey of the pastel-hued salt lakes in Victoria, Australia, and ‘Sand Sea’ – an exploration of the Namibian desert, whose ancient sand dunes are captured in soft

blush-coloured washes and in dramatic chiaroscuro.

The photographer notes that she is “drawn to deserts,” explaining that, “the Arctic is technically a desert – a desert of snow [rather than sand].” The scale of the desert is dizzying, we lose our sense of up and down, left and right, and the laws and rules of the man-made world no longer make sense. Ambiguous and unknown, Holm’s photographs could be a document of a planet other than our own or an imagined land. “People often say that my work feels otherworldly, and I love that – but, in fact, everything you see is actually here, and it needs to be protected.”

The first photographs of planet earth, taken on NASA’s Apollo 8 lunar mission, are credited with changing our understanding of the world, sparking the environmental movement of the late 60’s and early 70s. “We came all this way to explore the moon, but the most important thing we discovered is the Earth,” noted Astronaut Bill Anders. An alumni of NASA’s Artist-in-Residence programme – where she documented the agency’s US-based facilities – Holm’s photographs share the same function as the images of the earth as seen from space: a shift in perspective that introduces a sense of wonder to a subject towards which we feel over-familiar.

Like all great artists, there is a duality at the heart of Holm’s work. Concerned with matters of formal beauty – colour, shape, composition – the photographer offers arresting visuals, images that intrigue and attract, yet her work also probes at deeper questions – matters of ecology, politics and humanity. The contemporary designer and champion of sustainability, Gabriela Hearst, says it best: “Nature is the ultimate beauty, and beauty is serious.”